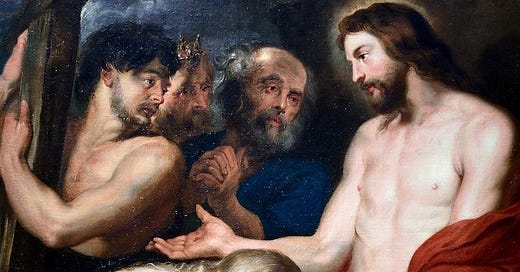

The Pharisees defend the sabbath, while Jesus puts an end to it—or so we often think. Mark 3 seems to fit this picture: The Pharisees watch in judgment as, on the sabbath, Jesus heals a man with a withered hand. The truth is, we have it exactly backward. The Pharisees revile the sabbath, while Jesus instead restores it. “Stretch forth thine hand,” he tells us in Mark 3, “and join with me in the eternal sabbath day.”

A withered hand is a terrible thing. It makes it hard to earn a living; for this man, it surely must have meant a life of hardship and of destitution. The Gospel passage tells us only of a withered hand; but in biblical terms, a withered hand implies a withered life.

A withered hand, in Scripture, is the embodiment of evil. Evil, according to Christian tradition, is privatio boni, absence of the good. Evil is the withering of life. According to the Law, you cannot be a priest and have a withered hand (Lev. 21:19). The logic is obvious: Evil may not come face to face with God.

A withered hand, then, means poverty, absence of God, paralysis of evil. One thing, however, is worse than a withered hand. “In the synagogue of the Jews,” Athanasius reminds us, “was a man who had a withered hand. If he was withered in his hand, the ones who stood by were withered in their minds.” The man stretches forth his withered hand, and Jesus heals him. The Pharisees close up their withered minds, keeping them out of reach of Jesus’s psychotherapy.

Jesus is Lord of the sabbath. That is what the verse immediately preceding this healing narrative tells us (Mark 2:28). It would be a strange thing for the Lord of the sabbath to abolish it. “Is it lawful to do good on the sabbath days, or to do evil? to save life, or to kill?” The answer should be obvious. A withered hand is evil, and it kills me. A hand restored is good, and it saves my life. A withered hand is a withered life; a hand restored is sabbath life.

It is the Pharisees that hate the sabbath, because they hate the sabbath’s Lord. Their minds are more withered than the man's hand, in need of sabbath healing. But in response to Jesus’s question, they are silent. The sickness of their evil minds has diminished them. Instead of opening their minds to the restoration of life, they determine to destroy the author of life himself, nailing his holy and venerable hands to the wood of the cross.

Kingdom is another word for sabbath. Jesus, Mark tells us, brings the kingdom. Just as he is Lord of the sabbath, so too he is King of the kingdom. And just as he heals our withered hands to make us fit for priestly sabbath service, so too he brings us back to his eternal kingdom.

We mess up our theology of sabbath with the type of questions that we ask: Does the sabbath law still hold for Christians? Did Jesus end the sabbath labor prohibitions? Is working on Sunday allowed or not?

Let me be clear: Pharisees abolish the sabbath; Jesus restores it. Pharisees are content with withered lives and collude with evil; Jesus heals, and by healing brings about the restoration of eternal sabbath.

The sabbath healing in Mark 3 presents the last of five sharp clashes between Jesus and the Pharisees at the beginning of this Gospel. Jesus’s martyr death is foreshadowed in these early conflicts.

We often follow the Pharisees in refusing to open up our withered minds to Jesus; we shrink our evil lives to nothingness while driving nails into his hands. Jesus returns us to his kingdom and heals our withered hands through restoration—apokatastasis (3:5). We long for all things to be restored—apokatastasis pantōn. Such healing is not hard to get. It is a matter of stretching forth our withered hands and minds to Jesus, looking for him to give us sabbath healing. He who has come to restore all things will give sabbath restoration to our withered lives.

(Originally published at First Things.)