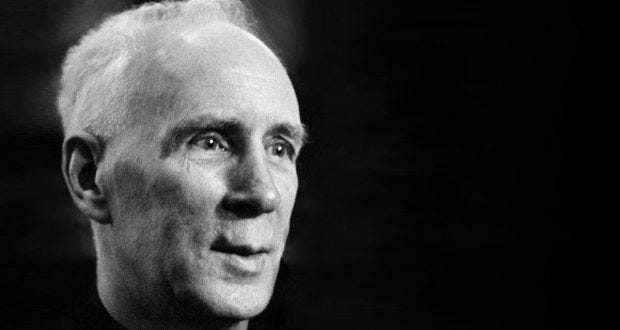

Henri de Lubac, S.J. (1896-1991)

Tradition measures changes in centuries. It is much too soon, therefore, to measure the impact that the mid-twentieth-century movement of nouvelle théologie had, either within or beyond the Catholic Church. Many will argue that the movement has been markedly successful in transforming the Catholic Church by means of the liturgical and theological developments in the wake of the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. For my part, I’d rather be cautious, and instead of focusing on nouvelle théologie’s success (or lack thereof), I think it more prudent, for now, to make a case for where and why I think the movement should be successful.

One way to explain nouvelle théologie is by describing it as a two-pronged attempt at renewal in the church. The first is that of ressourcement or retrieval, which took a variety of forms. The retrieval often focused on Thomas Aquinas, as in the work of Pierre Rousselot, Henri Bouillard, and Marie-Dominique Chenu. They all tried to rescue the Angelic Doctor from what they considered an ossified kind of Neo-Thomism that ruled the day. The church fathers were the other main source of inspiration, probably even more so than Aquinas. Henri de Lubac, Jean Daniélou, and Hans Urs von Balthasar all delved deeply into the fathers. Despite occasional differences among each other, they all looked to the early church for a reintegration of nature and the supernatural, which they believed Neo-Thomist theology had unduly separated.

The second prong is that of aggiornamento or updating of the church. For the church to have something to say to the world, the church had to speak to “the joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties of the men of this age,” as Gaudium et spes, one of Vatican II’s key documents, puts it. This meant that liturgically, culturally, and ecumenically, it was time for the church to let go of its perceived isolation. Aggiornamento served to join the supernatural realities of the church to the natural desires and longings of the world. To be sure, it is fair to say that Marie-Dominique Chenu and Yves Congar were much more on board with the aggiornamento agenda than were the Jesuits de Lubac, Daniélou, Bouillard, and Balthasar.

In light of the post-conciliar developments in the Catholic Church, we may perhaps conclude that the ressourcement project has had less success than the attempt at aggiornamento—although both elements have shaped the Catholic Church in a variety of ways through the decades that followed the Council. From my perspective, we could do with a whole lot less aggiornamento than we have had. It is hard to read Gaudium et spes today and not be taken aback by the naïve cultural optimism that it exudes. The social teaching of the Catholic Church has increasingly emphasized human rights, has virtually banned just war, has kept advocating for a world government, and, most recently, has substantially weakened its stance on homosexuality. When aggiornamento takes the “signs of the times” as its starting point, it runs the danger of rank accommodation to the surrounding culture.

Ressourcement, on the other hand—and in particular patristic retrieval—continues to hold great promise. The underlying drive here is the patristic conviction that nature is always already geared toward a supernatural end. It is this conviction that drove de Lubac’s controversial Surnaturel of 1946. Here and in many of his other publications, de Lubac argued for a sacramental ontology, maintaining that natural or visible things serve as sacraments (sacramenta) that render present supernatural or invisible realities (res).

In line with his sacramental ontology, de Lubac insisted that human beings have a natural desire (desiderium naturale) for the beatific vision. In other words, the supernatural final end was from the outset in some way inscribed in human beings. De Lubac may or may not have been correct in arguing that he had Thomas Aquinas on his side. But it is beyond doubt that he was in line with many of the church fathers, especially those of the East. They had all considered man as naturally good, so that that the beatific vision was in line with how God had created human beings. De Lubac, therefore, insisted that when divine grace assists in the process of justification, God acts on us not in a purely extrinsic manner but in line with human capacities that are already present.

We need de Lubac’s insights on the nature-supernatural relationship also today. Modernity has long assumed a gap between the two, so that we treat nature as strictly autonomous, as having its own natural ends, and as operating according to its own immanent natural laws. The result has been a truncated view of science, which ever since Francis Bacon has explicitly operated without regard for final (supernatural) ends. Thoroughly at home in the natural world and at liberty to pursue this-worldly enjoyments as ultimate, we have ignored and often simply denied that the happiness of God ought to be our final end. Still today, we need patristic theology’s asceticism and anagogical (upward-leading) focus.

The reintegration of nature and the supernatural—desperately needed in our empty, often nihilist world—implies a return to Christian Platonism. Platonism is often accused of metaphysical dualism—separating sensible things from otherworldly forms. The response to this objection is at least twofold. First, it ignores the significant fact that at the heart of the Platonic tradition (and especially of Plotinus’s philosophy) lies the notion of methexis or participation. Sensible realities exist inasmuch as they participate in intelligible realities. The Neoplatonic notion of participation is indispensable precisely to counter metaphysical dualism.

Second, we witness such dualism primarily not in Platonism but in modernity. We have replaced metaphysical realism (which is to say, the real existence of eternal forms or ideas) with metaphysical nominalism (where our naming of things is based not on their eternal nature or form but is the result of subjective constructs). In other words, by denying the real existence of species and genera, we now inhabit a world in which sensible things are the only things to which we have access—by way of empirical observation—while we think of intelligible things as beyond our reach, and therefore probably not worth investigating in great depth. It is modernity, therefore, rather than the Platonic tradition that is truly dualistic in its metaphysic. If we mean it when we claim that we want to get rid of dualism, we should back away from our modern understanding of reality and return to Platonic metaphysics.

De Lubac’s hermeneutical insights—based on his Platonic sacramental ontology—looked to the Old Testament as a sacrament containing the mystery of the reality of Christ. Following patristic and medieval theologians as his guides, de Lubac explained that the surface of the text contains infinite depths, which the reader is meant to uncover by means of spiritual exegesis. When the fathers allegorized Scripture, therefore, they did not arbitrarily impose an ill-fitting, alien meaning upon the text. According to de Lubac, allegorizing was a practice called for by the newness of the Christ event. Now that Christ is here, we are able to recognize the sacramental depth of the divine Scriptures, so de Lubac thought.

Biblical scholars, both Catholic and Protestant, have largely failed to follow de Lubac’s lead. It is not that they have examined his sacramental hermeneutic and found it wanting. Rather, de Lubac was a man far ahead of his time. The post-conciliar Catholic Church was much more interested in catching up with Protestant historical-critical exegesis than in retrieving patristic sources. And within Protestantism, evangelicals went through a phase in which they were keen to prove their exegetical prowess and academic qualifications, which led to a decades-long focus on authorial intent and historical reconstruction. It is only with the turn of the twenty-first century that theological exegesis has taken off and that de Lubac has received the fair hearing that he always deserved.

I have only scratched the surface. Retrieving nouvelle théologie is a worthwhile endeavor for many other, related reasons. De Lubac thought of the Eucharist as a sacramental meal that makes the church into the body of Christ. Congar treated tradition as sacramental time, which enables various, chronologically distinct moments in history to become contemporaneous within the one reality of Christ. De Lubac, Daniélou, and Bouilard all held to a notion of truth as sacramental reality—a sharing in the mystery of the eternal Word of God—an approach that necessitates a humble epistemology while also acknowledging the grounding of knowledge in the mystery of divine truth itself. Finally, Chenu recovered theology as a sacramental discipline, insisting that its purpose is initiation into divinizing union with God. I cannot unpack these developments here, but I sketch each one in greater detail in my book Heavenly Participation.

The sacramental mindset of nouvelle théologie is what makes it stand out, still today, as a unique source of inspiration. Nouvelle théologie’s sacramental ontology led not only to sacramental interpretation (patristic exegesis), but also to a sacramental meal (Eucharist), sacramental time (tradition), sacramental reality (truth), and sacramental discipline (theology). Every one of these lies anchored within a sacramental ontology—an understanding of reality that reintegrates nature and the supernatural. Nature and the supernatural are not two separate orders or levels, bridged perhaps by some kind of external link. Nature always already participates in the supernatural life of God; and God’s supernatural life is always already sacramentally present in the natural world.

Thank you, Hans. I am so grateful for your encouragement to read de Lubac. What a treasure.

Excellent! Thanks so much.