Philanthropy in the Desert

God's mysteries cannot be solved; they are meant to be lived instead.

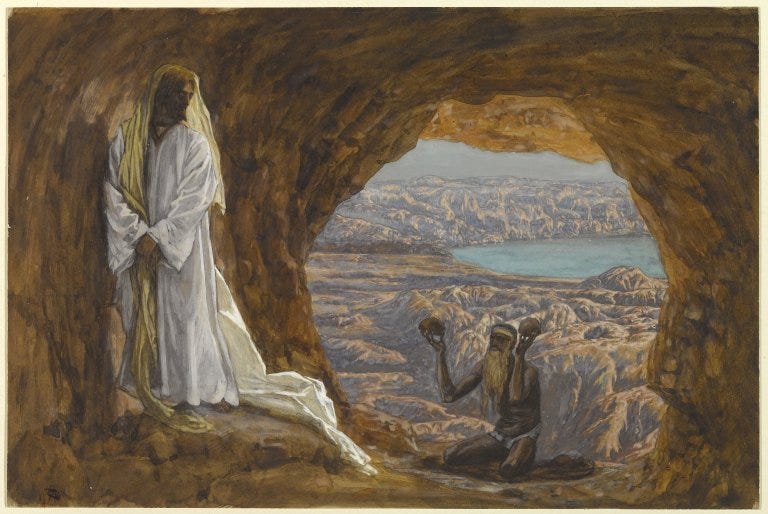

It is meet and right that Lent should start with Matthew 4. Its first sentence sums up not just Lent but the entire Christian life. “Then was Jesus led up of the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil” (Matt. 4:1). We may apply this to ourselves: “Then was I led up of the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.” Our brief span of life is the wilderness. The Spirit himself has led us here. His purpose is that we be tempted by the devil.

This sentence contains a great mystery: Why would God himself—the Holy Spirit—lead us into this world so that we might be tempted by the devil? I cannot solve this mystery, for God's mysteries are not like puzzles. They cannot be solved; they are meant to be lived instead.

When Jesus comes into the wilderness and the devil tempts him, he does not ask, “Why does the Spirit lead me here? What rational sense can I make of this?” What he does instead is fight the devil, with the Scriptures as his weapon.

Satan tempts Christ with three things: provision, protection, and power. What Jesus fights as he battles these temptations is the same thing we constantly fight ourselves: self-love (philautia). “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners” (1 Tim. 1:15). It is love for others—love for you and me—that made him come into this wilderness world. The incarnation, Maximus the Confessor reminds us time and again, is the result of Christ’s great love for man—his philanthrōpia. Giving in to temptation would mean a betrayal of this true love and a lapse into self-love: My bread, my safety, my status. Jesus, so he gloriously shows us in his wilderness battle, is driven not by self-love but by love for us.

The Spirit led him up into the wilderness because only by refusing the devil’s temptation, only by radically denying self-love, can Jesus be the savior of the world. It is his faithfulness despite temptation, his utter repudiation of self-love, that makes him the savior of the world.

To be sure, this still does not explain why God saves us in this way. Again, this is a question to which we do not have an answer. It is like asking why the devil tempted our first parents to eat from the tree of knowledge, or why the Israelites had to travel forty years in the desert with the devil always nipping at their heels. I do not know. Beyond doubt, however, self-love was Adam’s great undoing; and self-love continuously bedeviled the Israelites in the wilderness. Jesus is the second Adam; he is the new Israel, as well. Self-love did not spoil his forty days of fasting; self-love did not surface in his battle with the devil.

Saint Paul, in that other famous Lenten passage (2 Corinthians 6), paraphrases what it means to say “I was led up of the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.” Recall the setting of this letter. People in Corinth are challenging Paul’s authority as an apostle. The entire epistle, therefore, is a lengthy defense of his apostleship. In chapter 6, Saint Paul proves himself as a minister of God. The proof he has in mind is patience, afflictions, necessities, distresses, stripes, imprisonments, tumults, labors, watchings, fastings.

These may hardly seem apostolic qualifications. But for Paul, they are: How do the Corinthians know that Paul is a trustworthy apostle? How do we judge ourselves as faithful servants of God? By checking how we respond to hardship and temptation.

We are all, invariably, led into the wilderness. We know how Jesus responded: Not with self-love, but with love for us. We know how Paul responded: pureness, knowledge, long-suffering, kindness, the Holy Spirit, love unfeigned, the word of truth, the power of God.

Often we plead with God to just take us out of the wilderness, take the hardships away. But such is not Jesus’s prayer. Neither is it Paul’s. In fact, such prayers may well betray our self-love. It is, according to Saint Maximus in his epistle On Love, the most original of original sins: “Since the deceitful devil at the beginning contrived by guile to attack humankind through his self-love (philautias), deceiving him through pleasure, he has separated us in our inclinations from God and from one another, and turned us away from rectitude.”

Jesus, and Saint Paul along with him, are under no illusion as to why they are in the wilderness: The Spirit has led them up there to be tempted by the devil, for only fire removes dross from the gold; only temptation removes self-love from our human nature.

The misery of the wilderness is going to be ours till the last day of our lives. These forty days of Lent we face the question: When the devil comes to tempt me, how do I respond—with self-love or with true love? The virtue of philanthrōpia is the overcoming of philautia.

Letup comes only after the forty days are over—at the end of our worldly wilderness. This is the last verse of the temptation narrative: “Then the devil leaveth him, and behold, angels came and ministered unto him” (Matt. 4:11). Yes, temptation will give way to consolation, the wilderness will make room for paradise, and the devil will shrink back when angels come to minister. This is the great promise that the story holds out to us: Temptations will certainly end.

Lent reminds us that we are not there yet. For now, the devil and his minions ceaselessly harass and attack us. For now, we incessantly need to say no to self-love, to say no to the devil. The purpose of our lives is to counter self-love with true love—love for others.

And there is a second, crucial reminder in this Gospel passage: We see Jesus with us in the wilderness. We see him love us in the wilderness. The presence of his true love— philanthrōpia—gives us the strength to join him in his love.

(Originally published at First Things.)