Faith entails at least two things. First, it means to follow. John, the beloved disciple, looked into the tomb, saw the linen cloths, and believed (John 20:8). To believe is to follow John to the tomb.

Second, it means to love. Mary Magdalene, the Shulammite, the New Eve, heard Jesus’s voice and saw his face. She loves Jesus; she holds on to Jesus (20:17). To believe is to love Jesus and to hold on to him.

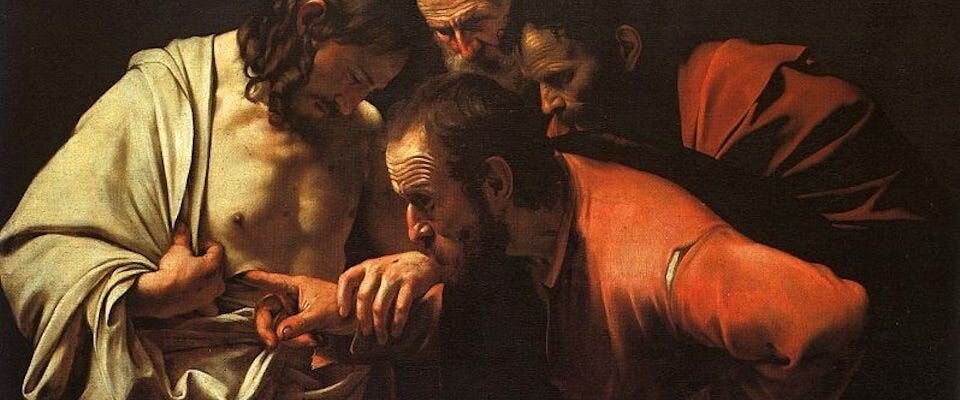

John and Mary are models of faith. But does the third vignette in John 20—Doubting Thomas—also offer a model of faith? In fact, to call him Doubting Thomas is unduly generous. He doesn’t even doubt. “We have seen the Lord,” the other disciples insist. Thomas’s response? “Unless I see in his hands the print of the nails, and place my finger in the mark of the nails, and place my hand in his side, I will not believe” (20:25).

When Jesus does, in fact, show up, he tells Thomas, “Do not disbelieve, but believe” (20:27). The contrast is clear: Thomas is an unbeliever, and he needs to become a believer. He mentions the marks of the nails in Jesus's hands and of the spear in his side not because he doubts but because he is convinced the whole idea is ridiculous. It’s like he is saying, “Imagine the absurdity of me putting my finger in his nail marks and my hand in his side. . . . I’ll believe it when it happens.” In other words, when hell freezes over.

Thomas’s unbelief is hardly out of character. When Lazarus dies, Jesus plans to travel south, to Bethany, near Jerusalem. His disciples don’t want him to go; they fear for his life. Thomas the Twin, in particular, puts up a protest. He says to his fellow disciples, “Let us go also, that we may die with him” (11:16). Thomas knows that to travel south is to go on a suicide mission. But if it has to be, then let’s go with him, so we may die with him. Thomas is a down-to-earth, dour character. He knows what it means to get yourself killed. And he knows, too, that death means the end.

In the Upper Room, Jesus tells the disciples that he is going to his Father’s house. It has many mansions, and he will prepare each of them a place. “You may be there with me; you know the way,” he says (14:4). To Thomas, this is pie-in-the-sky nonsense. “Lord,” Thomas calls out in frustration, “we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” (14:5). Thomas calls Jesus back to earth.

For Thomas, only one thing will do: empirical evidence. Sometimes Jesus just needs to be called back to reality: Travelling south means getting yourself killed; there’s no road connecting to mansions in heaven. Let’s stick with the facts.

Like John, Thomas is a committed follower of Jesus. Like Mary, he is fully devoted to the cause. But don’t tell Thomas that the eternal Sabbath is here. Don’t suggest to him he is already in Paradise. Don’t tell him time and space are reconfigured. Don’t tell him it is Easter, the Eighth Day, Paradise. Unbelieving Thomas, he won’t have any of it. People don’t rise from the dead.

But then Jesus shows up—“eight days later,” John tells us. Again, the reminder: It is the Eighth Day, the eternal Sabbath. Jesus stands among them, ignoring locked doors. “Peace be with you,” he says (20:26). The greeting makes real sense only in Paradise. Exactly a week ago, he greeted the disciples with the same greeting. Then he breathed on them (20:22), much as in Paradise: “The Lord God formed the man of dust from the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living creature” (Gen. 2:7). God had given Adam his Spirit, and now the New Adam, the gardener of Paradise, shares this Spirit with the disciples. “Peace be with you,” he says. Here is the Helper, the Holy Spirit; he will teach you all things. “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you” (John 14:27). The disciples share in Jesus’s breath, his Spirit; they are New Adams, every one of them.

When Thomas hears this greeting, gone is his big talk of putting his finger into the nail marks; gone all the bluster of putting his hand in Jesus’s side. He sees and believes: “My Lord and my God!” he calls out (20:28).

Thomas too is a model of faith, showing us that to believe in Jesus is to worship him. Thomas’s confession, “My Lord and my God!” takes the language that David used when worshipping God: “Bestir thyself, and awake for my right, for my cause, my God and my Lord!” (Ps. 35:23). It may have taken Thomas a long time to get there, but not even John or Mary made such a direct confession of Jesus as God.

No doubt, Jesus is human, Adam in his garden. But he is not only man: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (John 1:1). Now, near the end, Thomas makes that line his own. He believes, and in true resurrection faith, he falls down and worships.

John, Mary, and Thomas—no matter how much we may learn from them—are not perfect models. All three see first, and then believe. By contrast, we do not see Jesus’s grave cloths lying in the empty tomb. We do not see the gardener or hear him call us by our name. Nor do we see him suddenly show up in our midst and insist: “Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side” (20:27). Jesus, therefore, concludes with the comment, “Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe” (20:29).

John, Mary, and Thomas saw and believed; by contrast, we believe in the hope that one day we will see. It is a scary proposition: All we have is John’s word for it. These signs, says John in the last verse of the chapter, “are written so that you may believe” (20:31). We believe not because we have seen. Instead, we believe through John’s word (cf. 17:20).

John’s Easter narrative, then, leaves us with two questions: First, do we believe it is Easter? Do we believe it’s the Eighth Day? Do we believe we’re in Paradise? Second, do we follow? Do we love? Do we worship? For it is following, loving, and worshipping that together constitute resurrection faith.

*This essay was originally posted at First Things.